The Fede Engineering & Leadership Handbook

What is this?

I have terrible memory, so I make it a habit to jot down everything. This includes ideas I want to explore, I ideas I’ve validated and can’t afford to forget, and insightful concepts, explanations, and nuggets of wisdom I’ve come across from people smarter than myself. I then diligently store all this information in a searchable format. Instead of trying to boost my memory recall, I rely on the trusty Ctrl/Cmd + F shortcut to quickly find what I’m looking for. However, over the past 12 years, I’ve scattered these notes across numerous platforms and applications, forcing me to become my own makeshift SQL expert, performing manual JOIN operations to locate what I need.

The goal of this handbook is to act as a living document that keeps me honest and organized by forcing me to continue to update it in one accessible location. Also, I figured that if it helps me, it might just be useful for someone else too.

Effective Organization

A software engineering organization, in its simplest definition, represents a collective of software engineers assembled and coordinated to deliver valuable, functional solutions for a shared purpose. Constructing software engineering solutions is intricate, but the exercise of organizing humans to achieve a common is an even greater challenge. This challenge becomes even more complex with the growth of the team in the pursuit more ambitious objectives. The effective organization is the one that successfully manages to pull off this intricate orchestration at every stage during its existence.

An effective organization is like an explorer ship:

- Has a North Star that illuminates a distinct and clear purpose.

- Operates with an unyielding set of values and guiding principles to survive rough waters.

- Leverages a strategy as a map, which updates along its journey.

- Defines and follows policies, processes, and structures that support their quest.

- Continuously measures and verifies their position in their journey.

- Uses tools on every aspect of their voyage, from navigation to preventing mutiny.

In more traditional corporate language, an organization must have:

- Mision: What it does

- Vision: What it aspires

- Purpose: Why it does it

- Values: How it does it (philosophically)

- Strategy: The plan to achieve it

- Processes: How it does it (operationally)

- Policies: Rules to follow there

- Structures: How it organizes itself

- Tools: What it does it with

- Introspection: How it measures it is on the right track

Mission, Vision, and Purpose

Mission, vision, and purpose are three important concepts that define an organization. They are often used interchangeably, but they have subtle differences.

Mission is what the organization does and whom it serves. It is the organization’s reason for being.

Vision is what the organization wants to achieve in the future. It is a long-term goal that inspires and motivates the organization.

Purpose is why the organization exists. It is the organization’s core values and beliefs. It is what drives the organization to achieve its mission and vision.

Values

Every company has a distinct set of values, some are lengthy, others make great acronyms. What is imperative is that they are not just empty inspirational quotes on an “About Us” page. They should be your indivisible set of axioms from which you and the rest of the organization derives solutions to situations it has never seen before.

To see this in action, if one of your values is “winning is everything”, then you can expect behaviors that go outside the rules. Conversely, if “sustainability” is one of your core principles, then in situations like when deciding between two cloud providers you might choose the one with the smallest carbon footprint.

The following are the 8 values that I align with written in different styles. First column is mine, the others are rewrites courtesy of ChatGPT.

| Fede Style | Formal | Casual | Edgy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Never the Expert, Always the Student | Learning Mindset | Keep Learning Forever | Never Stop Fucking Learning |

| If it’s not a “Fuck Yes”, it’s a “Fuck No” | Empathy and Passion | Give a Damn | Give a Shit, Feel Passion |

| Discipline, Dedication, and Rigor | Dedication and Discipline | Stick to Your Guns | Discipline Like a Badass |

| Better in a Team than Solo | Teamwork and Growth | Teamwork Makes the Dream Work | Win Together |

| Comfortable with being Uncomfortable | Vulnerability and Humility | Stay Real and Humble | Embrace Vulnerability, Be Fucking Humble |

| Figure It Out | Resourcefulness and Tenacity | Get Creative and Never Quit | Get Shit Done, No Excuses |

| Good Enough, Never Perfect | Bias for Action | Just Get It Done | Relentless AF, Keep Going |

| Responsible Capitalism | Responsible Capitalism | Responsible Capitalism | Responsible Capitalism |

Strategy

“Engineering strategy is the discipline of making decisions about how to best use engineering resources to achieve a particular set of goals.” - Will Larson, Google Staff Engineer

A strategy is a roadmap for how the organization will achieve its goals, making the best use of its technical capabilities and taking into account its resources, and the competitive landscape.

A lasting strategy (e.g.: one that is not re-written every quarter) should be developed according to the following factors and in this order:

- Data

- Evidence

- Precedent

- Argument

- Instinct

Reviewing and updating your organization’s mission, vision, and strategy should be an ongoing process. You should regularly review them to make sure that they are still aligned with the needs of your organization and your stakeholders. The cadence will depend on the size and complexity of your organization and the industry that you serve. Typical cadence for software engineering organizations is 1 to 3 years.

Best Practices:

- Shouldn’t require mandating. Successful ideas spread.

- Should feel they were chosen because they were the best option.

- Should generate excitement.

- Should be defined around activities that influence results.

Results Based Management (RBM) is a management approach that focuses on achieving results rather than just following processes. It’s like aiming for the finish line instead of just running around the track. With RBM, you set clear goals, measure your progress, and make adjustments as needed to ensure you’re on track to achieve those goals. It’s all about getting things done and making a real impact.

- Outputs: What the organization puts out.

- Outcomes: The effect the output causes on consumers.

- Impact: The effect the outcome causes on our goals.

“Results-based management is the only way to run a successful software company. We need to focus on delivering value to our customers, not just following processes.” - Bill Gates, former CEO of Microsoft

Staging

Recognizing the right time for the right actions is crucial for achieving success. You might have all the right elements—people, tools, strategies—but if they aren’t utilized appropriately for the stage you’re in, it can lead to catastrophic results. The Saturn V rocket (so far the only vehicle to carry humans beyond Low Earth Orbit) had 3 distinct stages in its launch procedure. Had all stages fired simultaneously, we wouldn’t have been able to put 24 astronauts on the moon.

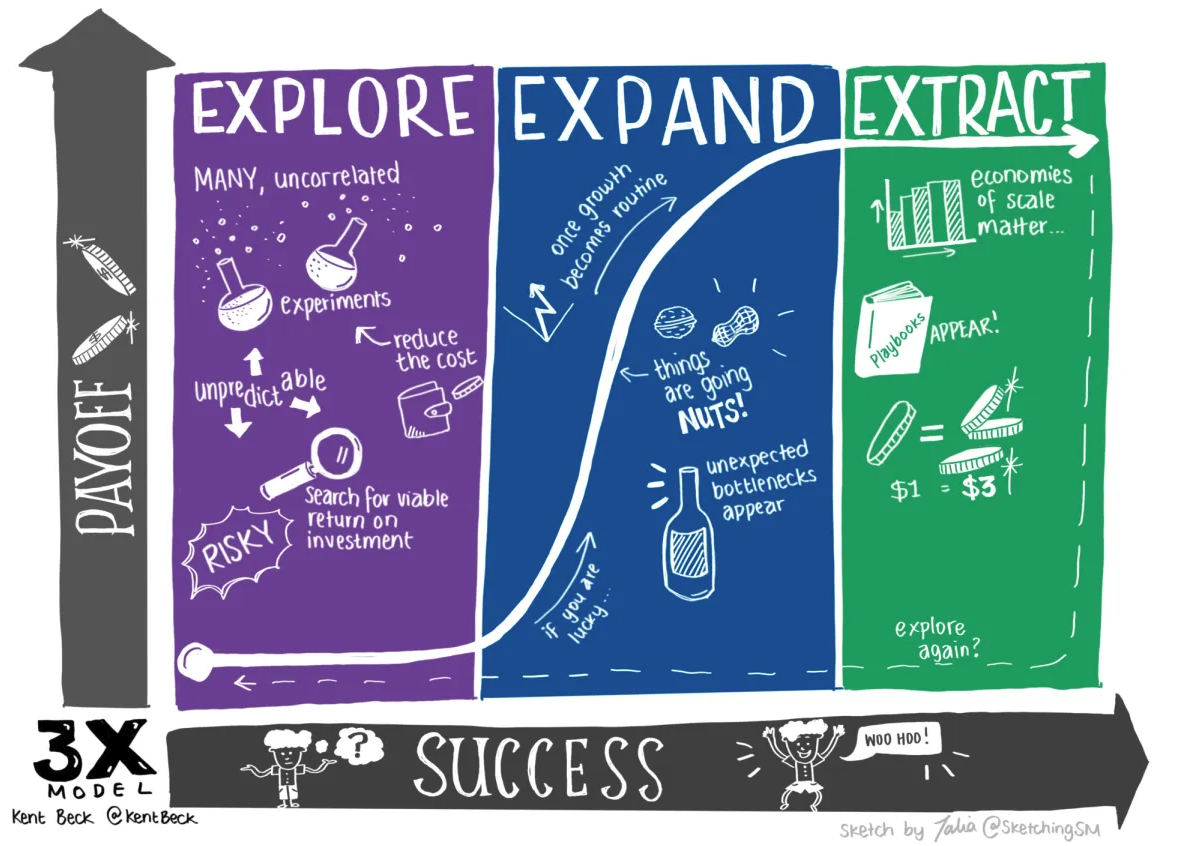

To achieve success, your actions and behaviors must align with the specific stage you find yourself in. Kent Beck’s 3X Model provides a practical framework for experimenting and innovating, breaking down the complex journey of “Product Develpment Triathlon” into three distinct stages:

Explore

- Tools: Iteration, testing, and experimentation.

- Environment: Uncertain, but adaptable

- Enemy: Risk.

- Goal: Disrupt inertia, combat disinterest, and discover a market fit.

- Activities: Maintain minimal costs, be cautious of local maxima (experiment success that won’t scale), and make choices that minimize the risk of change. Prioritize high iteration speed, low infrastructure costs, and flexibility for pivoting or scaling.

Expand

- Tools: Discipline and measurements.

- Environment: Awkward, but experiencing growth.

- Enemy: Bottlenecks.

- Goal: Identify the key rate-limiting resource, design structures and processes that will allow it to scale.

- Activities: Seek sustainable growth and early proof on how you could optimize without fully commiting. Remove blockages, solve infrastructure challenges. In case you applied Paul Graham’s “Do Things that Don’t Scale” during the “Explore” stage, figure out how to achieve the same results with actions that do scale.

Extract

- Tools: Specialization, and optimization.

- Environment: Stable, but change is risky.

- Enemy: Inefficiency.

- Goal: Fine-tune your system without compromising quality.

- Activities: Optimize your “Replicators” to achieve maximum output with minimal input. Focus on cost reduction, margin expansion, and the application of economies of scale, to deliver your product or service at peak efficiency (low cost, high quality).

Navigating this triathlon, or any triathlon for that matter, presents a unique challenge. Each phase demands its own set of tools, expertise, and measurement systems. A bicycle won’t serve you well in the water, becoming a faster runner doesn’t automatically make you a faster swimmer, and the way you measure progress shifts from miles per hour on a bike to seconds per 100 meters in the water. Moreover, these phases are distinct and don’t overlap; just as you wouldn’t attempt to swim with running shoes, the critical moments occur at the end and beginning of each phase as you establish your rhythm and during the transitions between them.

In the context of an engineering organization,failure to recognize which stage your idea, product, organization is at can be disastrous. Furthermore, you can have success in one stage to then fail categorically on another one. Particularly in the context of people. Is the same team supposed to transition throughout all phases? If so, you better focus on hiring triathlonists. Or can you move along the product and specialize three distinct teams of Explorers, Expanders, and Extracters?

Kent Beck’s 3X visualized by Talia @sketchimgSM

Kent Beck’s 3X visualized by Talia @sketchimgSM

Goals

Having the appropriate goals that align with the scope, context, and stage can motivate a team to incredible success. Conversely, misaligned and overly ambitious goals lead to frustrating conflicts and failures. Several popular acronymized frameworks aim to help with setting, tracking, and achieving goals:

- SMART: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. It emphasizes setting goals that are clear, quantifiable, realistic, and time-constrained.

- OKR: Objectives and Key Results

- BHAG: Big Hairy Audacious Goals from “Built to Last” by Jim Collins

- 4DX: 4 Disciplines of Execution by Covey, the author of “7 Habits of Highly Effective People”

- GSM: Goals, Signals, and Metrics from Google

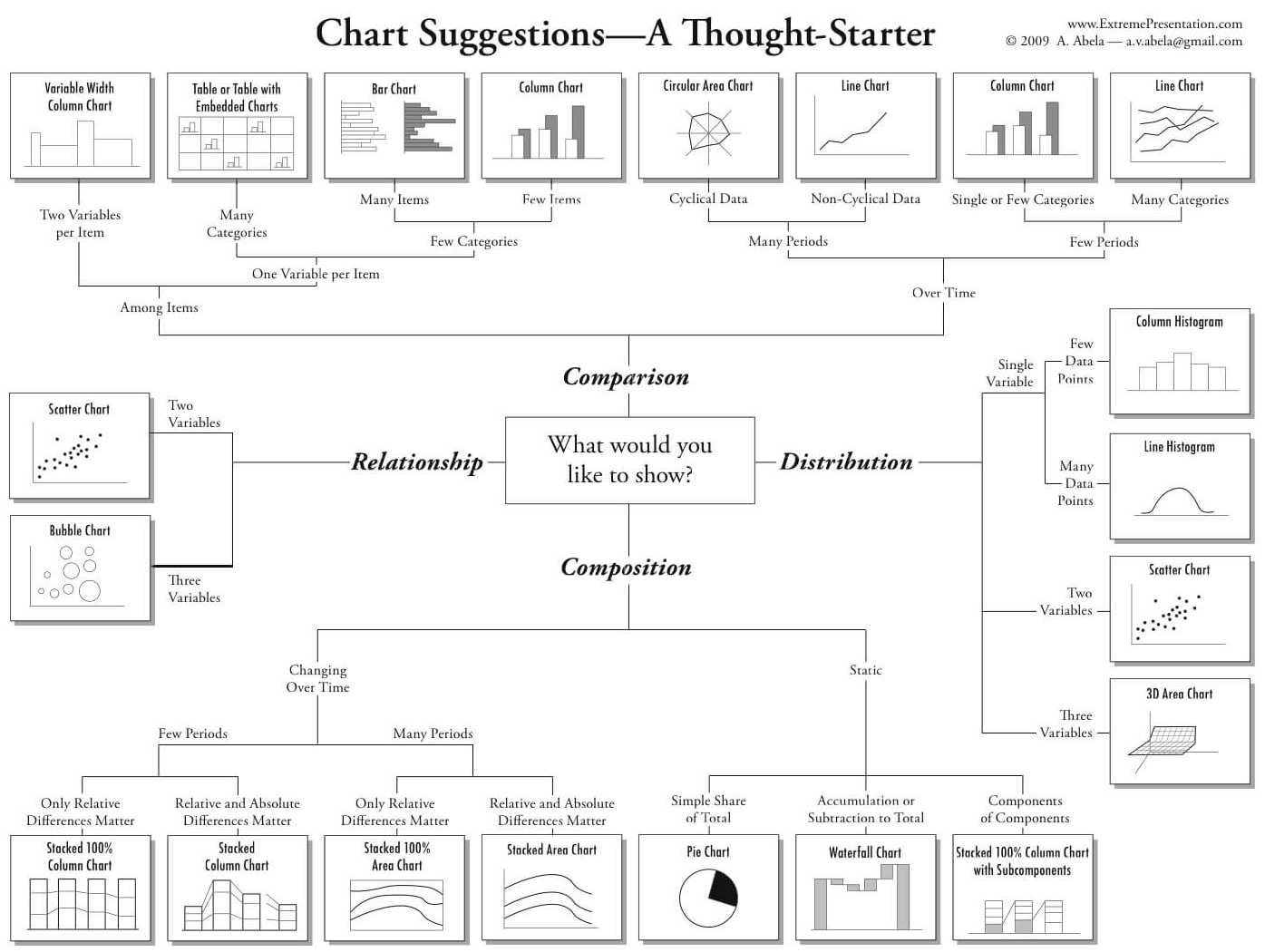

While these frameworks are valuable tools, a great tool for the wrong job builds nothing. A goal can be an ambitious vision, a clear mission, a focused business objective, and even a specific target. They all share a common element: a definition of “done” or “success.” To understand the nuances, it helps to analyze the scope of the goal, whether it’s a grand aspiration or a specific task.

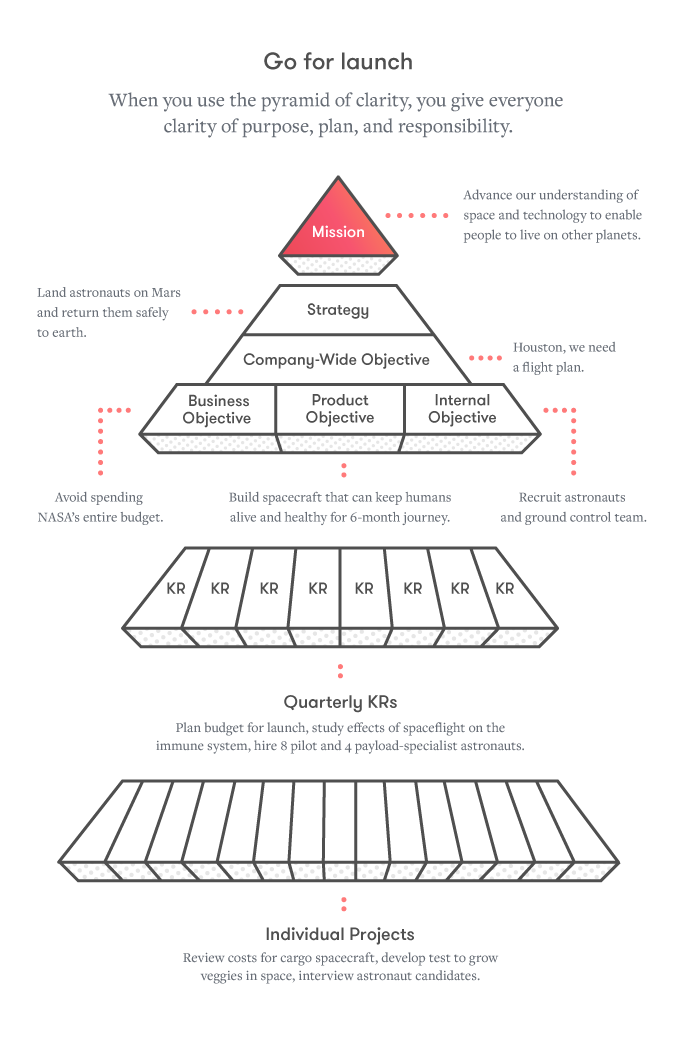

Dustin Moskovitz, founder of Asana, leaders in work management, created the “Pyramid of Clarity” as their way of decomposing goals:

https://wavelength.asana.com/pyramid-clarity-strategic-alignment/

https://wavelength.asana.com/pyramid-clarity-strategic-alignment/

The mix of terminologies surrounding this subject can get confusing: goals, objectives, deliverables, targets, results, measurables, and metrics. However, not all of these terms are interchangeable or share the same characteristics. In fact, some of them can exhibit varying properties based on the specific context in which they are used. What they all have in common is that they offer a definition of ‘done’ or ‘success.’ So, how can we break this down? What exactly are you measuring and tracking? Is the goal the entity you’re directly tracking, or is it a breakdown of measurable targets that collectively lead to achieving the goal? If it’s the latter, how can you ensure that you are measuring the right metrics to progress toward the goal?

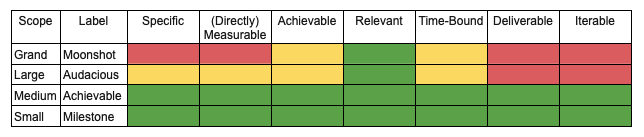

This is a table I created a long time ago to help me work through the terminology:

This decomposition extends the SMART model to analyze various types of goals. Technically, every goal is measurable in the sense that it should have a defined criterion for success. However, the term ‘directly measurable’ implies a different level of clarity. Let’s consider the distinction between having a broad goal like ‘being healthy’ and a more specific one like ‘maintaining a body temperature of 99°F for 99% of the year.’ Furthermore, the ability to control or deliver a goal distinguishes it from being an objective or a target. While you can’t directly control your body temperature, you can control how often you work out or manage your calorie intake during the week.

The following is my adaptation of Google’s GSM process with OKRs for creating “Nested OKRs” or “MOKRs” (Moonshot OKRs). I’ve found this approach to be highly effective for consistently developing , as it helps guard against the ‘streetlight effect’ of only focusing on what’s immediately visible, thereby reducing the risk of setting misaligned goals and unattainable targets:

- Goal: This represents the desired outcome, typically at a high level and devoid of technical specifics.

- Signal: These are the objectives you’d like to measure, although you can’t directly control them.

- (Actionable) Targets: These are the specific deliverables you can both measure and directly influence.

This model enables you to quickly assess whether you’re on the right track and, if not, why you might be falling short. Your “Actionable Targets” should be executed in parallel and break down into deliverable milestones. They should be designed such that, based on a set of validated assumptions, each has the capacity to drive the signal in the desired direction.

Ideally, the “Signals” should be monitored in real-time as the “Actionable Targets” are being achieved. This enables you to simultaneously validate if these deliverables are moving you closer to your “Goal”. If the “Signals” aren’t heading in the right direction despite hitting your targets, it suggests that the assumptions behind your defined deliverables may have been incorrect or improperly implemented. The latter can sometimes result from failing to include paired indicators that avoid unintended negative consequences on the overall “Goal” and its associated “Signals”. For instance, if your “Goal” is to reduce losses due to fraud, it may lead you to treat everyone in your checkout flow as a potential fraudulent agent. This approach should aligned with other “Actionable Targets” such as false-positive rate and customer satisfaction scores.

Putting it all together, here is a simplified example from a startup I co-founded:

Moonshot Goal: Become the #1 ready-made meal delivery service in Austin, TX.

Audacious Goals/Objectives/Signals:

- Increase website first-time conversion rates from 5% to 30% within 2 years.

Achievable Goals/Key Results/Actionable Targets:- Achieve less than 1% checkout flow error rate within 12 months.

- Reach less than 200ms response time for all pages within 10 months.

- Implement A/B testing to optimize site layout and iterate until achieving drop-rates below 20% within 6 months.

- Achieve delivery efficiency of less than 1% late deliveries within 1 year.

Achievable Goals/Key Results/Actionable Targets:- Build a delivery clustering algorithm that keeps all deliveries within 5 minutes of each other within 12 months.

- Perform inspections of 90% of the delivery fleet every quarter

- Achieve customer retention rates of 80% in within 1 year.

Achievable Goals/Key Results/Actionable Targets:- Launch subscription billing model within 12 months.

- Identify and address outliers in dish feedback from the weekly customer survey, to reach less than 10% of dishes with a z-score exceeding 1.5 standard deviations from the mean mention rate within 8 months.

- Mantain employee churn below 5%.

Achievable Goals/Key Results/Actionable Targets:- Conduct quarterly engagement surveys with a minimum 85% response rate.

Note that even the Actionable Targets can be further decomposed into milestones. These are usually the implementation details of each team responsible with each target.

Effective Growth

Companies, divisions, departments, all operate an exists on a transient state. The organization that resists change, or doesn’t seek it, is one that at best, is not destined for greatness, and at worst doomed to failed sooner rather than later. Constant evolution and change is literally baked into the fabric of our reality (2nd Law of Thermodynamics). However, unbounded growth is cancer. It is in the transition between one stage to another where an organization is most at risk of introducing cracks in its foundations. The key characteristic of any successful enterprise is the effective handling of its growth and scaling journey.

“The efficient organization has sub-linear resource cost growth as it increases in scale.”

Unfortunately, the answers to this problem are very specific to each organization. Yet, there are a number of practices that if implemented correctly, can unlock teams and leaders to scale effectively:

- Satisficing

- Aligning

- Auditing

- Incentivizing

- Knowledge Sharing

- Async-ness

- Heuristic-Driven Values (Policies) / Value-Aligned Heuristics

- Growth-Focused Processes

Satisficing

Getting distracted is not just procrastinating on social media, it’s losing focus on your main quest and chasing side ones. This can mainly happen due to two behaviors:

- Not measuring the correct thing.

- Not being comfortable with saying “good enough”.

https://modelthinkers.com/mental-model/satisficing

https://modelthinkers.com/mental-model/satisficing

Switching from being a Maximiser to Satisficer can be very difficult. Here’s a useful practice: Go running with one shoe slightly untied. It can feel uncomfortable but if your pace is not affected by it, don’t stop. Your goal is to complete your run in the shortest time possible, stopping in this case is guaranteed to affect that goal negatively, the only purpose of this action is to reduce your uncomfortability. The requirement is to mantain a specific pace, if you have satisfied that goal then don’t try to maximize.

Aligning

The practice of “aligning” is a fundamental concept in ensuring that actions, behaviors, and decisions within an organization are in harmony with its goals, values, and the broader context. This practice is essential for maintaining cohesion and preventing potential conflicts.

Alignment involves several key elements:

- In Service of Current Goals: Actions should contribute to achieving the organization’s current objectives.

- Embodying Values: Decisions and behaviors should reflect the core values of the organization.

- Avoiding Conflict: Alignment seeks to prevent conflicts or contradictions with other teams or departments.

- Facilitating Future Decisions: Actions should be forward-thinking, contributing to the organization’s adaptability and future readiness.

This practice can take many shapes depending on the situation. Here are a couple examples:

When defining team goals and metrics: Imagine an e-commerce platform with a team responsible for the Billing process. If they define the team’s goals to be around story points, velocity, or the number of features, they will get teams focused on churning out code without regard for quality, customer satisfaction, or collaboration. They will maximize metrics they are being measured against. Instead, consider if, in the case of that Billing team, some of their metrics were: dollars unrealized during the checkout experience and customer support calls regarding issues in the billing process. Now, this team is aligned to maximize quality and customer satisfaction. It’s not about code for the sake of code, but about what features or optimizations will streamline the checkout process in such a way that more purchases are completed (fewer bugs, less friction in the funnel) and in a way that leaves customers happy and satisfied (fewer frustrated calls).

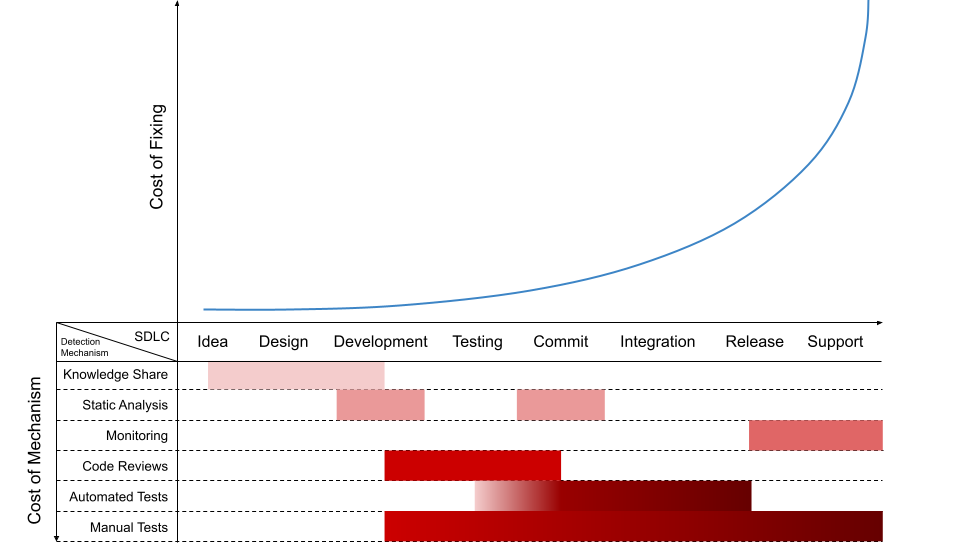

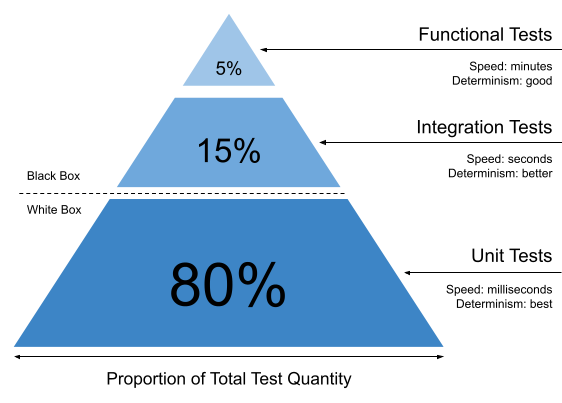

When defining organizational policies: An engineering department may establish a minimum code coverage requirement. At a simple glance, it’s a policy to motivate and incentivize quality through the quantity of testing. However, it disregards the quality of the testing and the impact that maximizing this one metric could have on the time to complete testing and deploy code. This policy is missing alignment with the complete goals for the department, namely deploy time. Conversely, if the policy focuses on “efficient, high-quality testing,” it could track the rate of bugs reported in production alongside the time to complete a deploy. This empowers engineers to keep only a specific suite of high-signaling-error-rate tests. It also opens the door to creative solutions to the problem, perhaps with parallel running of tests. However, this would likely have an impact on infrastructure costs, presenting another opportunity to enhance alignment if there is a tight budget.

The important consideration is that there’s no one perfect solution in the practice of aligning. The critical factor is always to consider the breadth, scope, lateral impact, and the potential unintended consequences now and in the future.

Incentivizing

Aligning your incentive structures and recognition methods with your desired outcomes and values is another crucial activity. It’s essential to ensure they do not center around vanity metrics that can be manipulated and bring no tangible value to the business, customers, teams, or individuals.

For instance, if recognition is exclusively tied to outcomes, it can foster an organizational culture lacking in boldness, creativity, and innovation. However, recognizing both successes and failures resulting from ambitious attempts at lofty goals helps cultivate a culture that appreciates both risk-taking and resilience.

Incentives can inadvertently promote individualism, so it’s vital to use them as tools for fostering a culture where individuals support each other’s success and don’t let each other fail.

It’s critical not to reward relationships. If people perceive that advancement in your organization is primarily determined by who they know, it can lead to a culture of bloated calendars and meetings, suck-ups, and vanity metric reporters.

Recognize and reward both outcomes and efforts. Neglecting to acknowledge efforts can lead to team burnout. Keep in mind that efforts and results are interrelated, and recognizing both helps maintain a balanced and motivated workforce.

Moreover, don’t rely solely on extrinsic motivators. Instead, remove barriers and provide opportunities for individuals to self-motivate with the three intrinsic motivators:

- Mastery: The desire to improve and excel.

- Autonomy: The desire for independence and self-direction.

- Purpose: The desire to contribute to a greater cause.

Consider these examples:

Hackathons: Conduct them yearly or quarterly, where individuals or teams can work on projects they’re passionate about and present them to the organization. These projects might even lead to new products or features.

Open Source Contributions: Encourage contributions to open source tools used by the organization or release internally developed tools as open source projects. Note that maintaining open source projects comes with responsibilities.

Peer-to-Peer Celebrations: Implement a system for employees to nominate or recognize their peers, either anonymously or not. Can be in real time or tallied across a Sprint and those with the most votes are highlighted during Sprint kick-offs.

Audits

The most common reason as to why we do something in a certain way, is because we have always done it like that. What’s more, circumstances and contexts change over time but we don’t adjust accordingly. Inertia is the root of a lot of inefficiencies. To combat it, routinely audit people and organizational activities. It’s a simple process of asking certain questions or taking a step back to review if there have been some inefficiencies creeping slowly over time.

Some areas to audit regularly:

Calendar

- Are you context-switching too much?

- Action: Group 1:1s together in one day

- What is 80% of your calendar going towards?

- Action: Should be spent towards your top 20% goals

- Are you having to work after hours to be able to focus?

- Action: Block-off time for important but not urgent work

- Are you maintaining a good work-life balance?

- Action: Mark your working hours and do not reach out to others outside of theirs. Lead by example.

Meetings

« TODO! »

Types of meeting based on their : To motivate/inspire/celebrate To share knowledge/broadcast: Info not everyone will open in an email To brainstorm: To make a decision Must have a written proposal first. Only when async is too inefficient To sync/agile

Energy

Evaluate all your activities and divide them into:

- How much energy they give or take

- How much they contribute to goals

You will find they can be grouped in four main categories:

- Wasters: If they make you feel drained and provide little to no value towards goals.

- Action: Eliminate

- Procrastinators: They make you feel energized but provide little to no value towards goals:

- Action: Delegate if they are important. Eliminate if not important

- Chores: They make you feel drained but contribute towards goals:

- Action: Automate if possible. Do early in the week if not

- Achievers: They make you feel energized and contribute towards goals.

- Action: Since these are the most enjoyable and impactful to you, likely they will also be for others, delegate them if possible to embody a servant and growth-minded leadership. If nobody else can do them, then schedule them for later in the week.

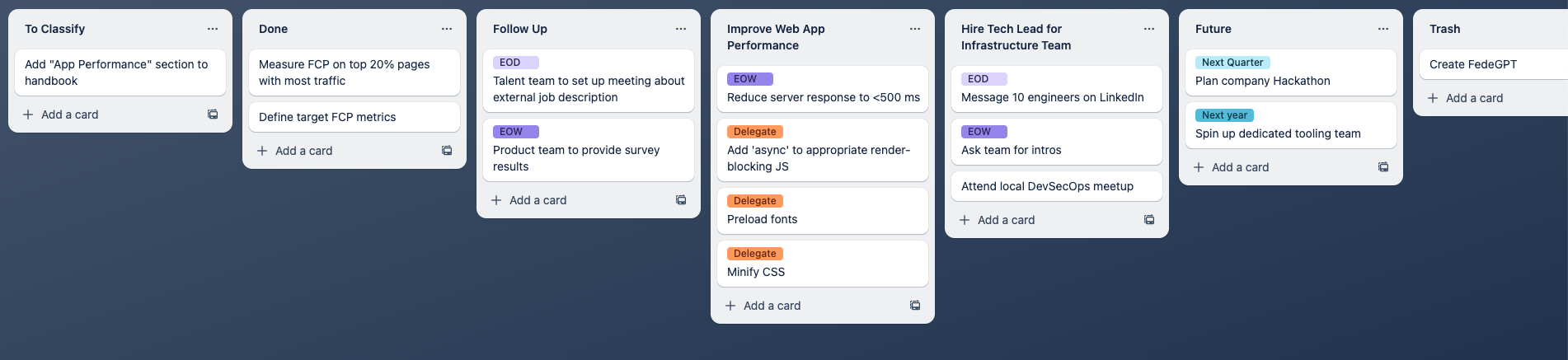

Self-Organization

Set yourself a good system for managing your workload and getting things done. Consider the following Kanban implementation of the Getting Things Done (GTD) model:

Collect The first column in your board should always be “To Classify”.This is your inbox of ideas, of actions, of reminders. Don’t filter.

- Process Before you start every week and at the end of every day, you will go through your “To Classify” column and determine a course of action:

- If not towards an immediate goal:

- Mark it as “Future”

- If useless:

- Mark it as “Trash” and keep notes as to why

- If a “you” task:

- If you can get it done immediately, do so and mark it “Done”

- Otherwise, assign it to the respective goal with priority and deadline/date

- If a “delegate” task:

- If you can delegate immediately, do so and mark it “Done” or “Follow Up”

- Otherwise, assign it to the respective goal with priority and deadline/date

- If not towards an immediate goal:

Follow Through This is the most important step! It’s where you actually take action on the items on your lists.

- Repeat Do it every week.

Decisions

Some best practices:

For every major decision, create a document recording the circumstances, inputs, analysis, and all considered options. Review this document if any of the circumstances and inputs change down the road.

Should always be made at the lowest level possible.

Making them doesn’t require the most senior, it requires the most knowledgeable.

Teams constantly slowed by decision-making are indicators of:

- Unclear objectives

- Unclear strategy

- No confidence and people want the burden on someone else

Async-ness

One of the main tools to effectively navigate either the fully remote or hybrid mode of working that is without a doubt the way of the future, is to instill healthy asynchronous practices. What this means is adding an extra consideration before initializing any activity or process that requires people to interact: “How can this be done asynchronously?”. For example:

Instead of immediately scheduling a meeting to discuss a potential decision, consider, “Can this be handled in a live document?” or “Can we at least get started in a live, online document and have a shorter more efficient meeting later?” Instead of locking an entire team in a stand-up because everyone is waiting for their turn to ask a question, consider “Can I post my question in the group Slack channel and someone can answer when they have time?”

An even greater consideration that organizations need to be clear on is, do you operate in a “follow the sun” model or a “universal timezone” one? With follow the sun, functions and teams are organized around their physical proximity, allowing them to work within normal working hours. Conversely, a universal timezone approach requires everyone, no matter where they are, to work during a certain timerange, usually around the timezone of the main offices. There are pros and cons for either. What’s important is making sure it is decided and that everyone has buy-in.

Knowledge Sharing

In an engineering organization, knowledge is the most valuable yet intangible asset. Therefore, the organization must cultivate a culture, establish processes, and implement policies that facilitate the recording, updating, and sharing of knowledge to enable scalability. Otherwise, this invaluable asset may be lost.

“Knowledge is viral. Experts are carriers.”

Knowledge sharing is one of the most scalable activities when we consider the time spent creating and maintaining knowledge versus the cumulative time saved when others read and utilize it.

To achieve this, it is imperative to build a self-reinforcing loop of knowledge. An organization should encourage experts to record and distribute their knowledge. Simultaneously, leaders play a pivotal role by creating rituals, mechanisms, and incentives that promote knowledge recording and distribution. These efforts result in the growth of more experts and leaders who value knowledge sharing.

Some of the common challenges to creating an effective culture:

Lack of Psychological Safety: Many engineers may feel inadequate or unqualified to openly share with others. The risk of being ridiculed if there’s a gap or mistake in knowledge can be a powerful agent holding them back.

Fragmentation: Information scattered across various platforms can lead to inefficiencies.

Mimicry: Some individuals may copy patterns without a deep understanding, leading to knowledge gaps.

Graveyards: Inactive areas of knowledge that hold little interest for the team.

Knowledge can be distributed through different means:

- Personalized: Tailored one-on-one or through mentorship.

- Documented: Asynchronous, reaching many through documents and videos.

- Professorial: Synchronous, educating a broader audience.

Each type has its trade-offs, such as personalization vs. generalization, scalability vs. maintainability, and conciseness vs. brevity.

Recorded knowledge, such as documentation, is a cornerstone for remote work. Highly organized, indexed, and searchable documentation is vital for high productivity, while continually evolving documentation is key to successful scaling.

Furthermore, recorded knowledge can come not just from formal writeups, but even by being intentional to do so within normal informal activities:

- A policy to enforce using public Slack channels as much as possible. GitLab goes as far as having a dedicated metric tracking how many DMs are sent in private channels.

- BCC’ing external communications to a team’s email list so everyone can stay informed.

- A process to clear Slack channels every month or so to ensure people keep the organization’s knowledge base updated.

Heuristics

These can range from well defined guidelines that dictate how certain procedures should be carried out (e.g.: escalation policies, HR policies), to more abstract heuristics that embody living examples of the company values (e.g. “open door policy”).

Many an organization proudly display and boast their values externally and internally, yet does nothing tangible to apply them. This is where company sanctioned heuristics (or policies) come into the fold. Here’s a shortened version of the definition from Wikipedia:

“Any approach to problem solving or self-discovery that employs a practical method that is not guaranteed to be optimal, perfect, or rational, but is nevertheless sufficient for reaching an immediate, or approximation in a search space. Heuristics can be mental shortcuts that ease the cognitive load of making a decision.”

Simple and concise company-sanctioned heuristics make your day just that much easier. Research shows that we have a finite amount of decisions we can make per day, going beyond that and our judgement in making further decisions declines. This policy-driven approach saves you time and cognitive power. When faced with situations that fit the bill, don’t have think about it, just follow the company policy.

As you can see, this follows from the “sufficing” practice, but it can also follow the “aligning” practice. Each of your heuristics should correspond to one or more of your defined values.

| Value | Heuristics |

|---|---|

| Learning Mindset | “If there’s something you don’t like doing, become the best at that thing” |

| Care Deeply | “If you are going to do it, do it to the best of your abilities” “If you liked it, you should’ve written a test for it” |

| Dedication and Discipline | “Hope is not a strategy” |

| Teamwork and Growth | “Always assume good intent” |

| Vulnerability and Humility | “No blame” “Sunlight is the best disinfectant” |

| Resourcefulness and Tenacity | “Failure is welcomed if you learn from it” |

| Bias for Action | “Always ask for help, but you better have attempted something first” |

| Responsible Capitalism | “All else being equal, choose different over the same” |

Effective Hiring

“I am convinced that nothing we do is more important than hiring and developing people. At the end of the day you bet on people, not on strategies.” - Lawrence Bossidy, former Chief Executive of General Electric and Honeywell

It starts here. An organization’s number one asset is its people. Products pivot, strategies evolve, code can get sudo rm -rf‘d, names and logos can be changed. However, people are what make a company. The right people not only lead to success, but they make the journey a lot more enjoyable. Whereas the wrong people can not just make the journey slow and painful, they can outright stop it.

Unfortunately, the size of a workforce and the perception that a company is constantly hiring have become vanity metrics for success. This couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, your effectiveness as a leader is measured by your ability to leverage and achieve more with less. An organization is a system of people working together to achieve a shared goal. They are not being hired to work in silos, therefore, consider the combinatorial explosion of adding a new person into your system. The number of unique possible connections in a network of n people can be calculated with n(n-1)/2. The complexity and costs in communication grow polynomially (quadratically with respect to n). This is a bit of an oversimplification because every person added is not talking to every other person in an organization. Still, the point to consider is: Only if the value-added greatly surpasses the increase in internal complexity, should you consider hiring.

Henry Ward, CEO and co-founder of Carta wrote a great one-pager on hiring, and his first principle is: “Hiring means we failed to execute and need help”.

Now that the gravity and importance of hiring have been stated, how do you hire? What does “the right people” mean? Who are they? How do you find and identify them? How do you bring them into your company? And how do you grow them so they continue being “the right people?” The answers to these questions is the hiring process.

General Guidelines

Hire for value fit over culture Cultures evolve (or should), values don’t (or shouldn’t). Alignment on a north star is achieved through shared values and the culture is the aggregate of everyone’s way of thinking and acting. Hiring for value fit assures you that you don’t have to micromanage or interview for every possible scenario they could encounter. You trust their judgment.

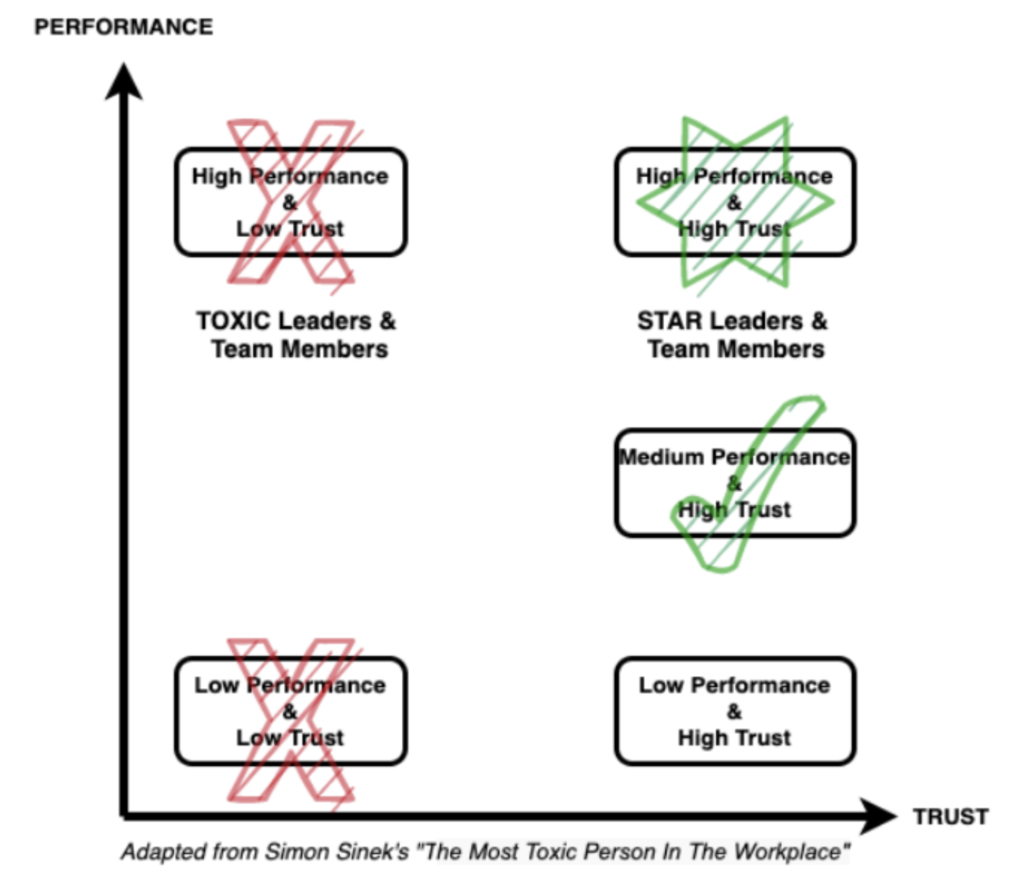

Hire for trust over performance Simon Sinek has a great video on how Seal Team 6 selects their members. They prioritize trust among team members over individual performance in building high-performing teams. This doesn’t mean not caring about performance, but that in order to construct the most high-performing teams, focusing on the trust among the members is more important than their individual performance. One way to identify high-trust leaders during interviews is to look for leaders who are honest, accountable, competent, humble, and empathetic.

Hire collaborators over soloists To build a high-performance team, you must hire individuals who find value in being part of a team. This is especially relevant for junior engineers who have not yet been part of a high-performance team and therefore see teamwork as secondary. These engineers are more focused on measuring their output in terms of lines of code, PRs merged, or tickets completed. During interviewing, probe around their most rewarding professional moments and what makes work enjoyable and listen for any mentions of collaboration.

Hire intrinsic over extrinsic motivators There are three parameters to calculate the horizontal range of a projectile (\(vo^2sin(2\Theta) \over g\)). Just like we approximated the volume of a chicken to be a sphere in Physics II, we can use projectile mechanics to estimate how far an engineer can go. If you want someone to go far is best to have high initial velocity, pointed the closest possible to the ideal direction, and minimize the deacceleration. In this contrived example, the deacceleration is the inevitable loss of motivation that we experience as humans as we go about any process. The responsibility of the leaders in your organization is to find people with the right initial velocity, point them in the right direction, and motivate them to minimize this drag. This becomes incredibly difficult if the person is motivated from external factors (money, praise, accolades) versus from within.

Hire “launched with (some) defects” over “launched when no defects” Conversely a projectile is not getting anywhere if it never launches. Often times engineers also tend to be perfectionists waiting for near-perfect conditions to deliver or release a product. Those who are comfortable with the process of learning, are comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Don’t forget, technical skills can be taught, and certain softer skills can be coached, but some traits are innate. Teach a man a technology and he’ll eventually become obsolete, teach a man how to teach themselves, and they’ll always be in need.

Process

Hiring is complex. You want to spend the least possible amount of resources to find the strongest signal that someone will be effective in their potential new role and organization. It should never be an attempt at clairvoyance, but a consistent and standarized methodology for the following key reasons:

- Eliminates bias

- Yields more consistent results

- Makes it measurable and therefore improvable

- Can be replicated as the organization grows

These are some fundamentals I’ve gathered over the years.

For hiring process:

- Dont create a process to find more yous. Create a process to find what you really need.

- What you need is not a title, is a set of outcomes.

- Half-assing it will considerably affect the results. Don’t force employees to participate in the hiring process if they don’t care to do it.

For crafting a role:

- Define it around outcomes.

- Be honest about the state of your organization and the desired outcomes and determine if this role is set up for success.

- If it would take someone in the top 1% of their field to achieve this, consider if you can compensate them accordingly.

For consideration during the interview process for each person:

- Can they individually be so productive that they raise the average team productivity output?

- Can they be a multiplier for everyone else?

- Is this person’s best work behind them or in front of them in their career?

- Does this person have 90% chance (high likelihood) of achieving the outcomes that only the top 10% of candidates could achieve?

- Who is on a team matters less than how the members interact. Does this person fit the team they would be a part of?

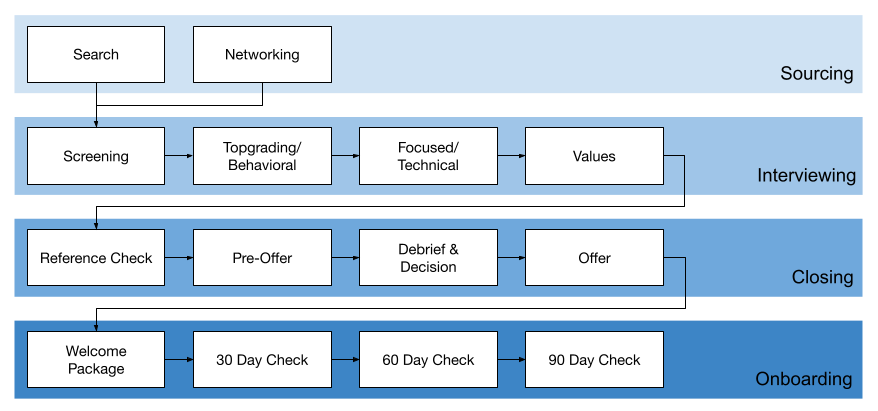

Here are my steps, crafted mostly from “Who: The A Method for Hiring” by Geoff Smart and Randy Street.

Role Proposal Document

Create a role/position proposal document with the following sections

- Goals

- Clearly define the expected outcomes with 3 to 5 SMART goals. Decompose each goal into:

- “We would be satisfied if you hit this target”

- “We would be impressed if you hit this target”

- “We would change our company logo to your face if you hit this target”

- What resistances will this role encounter?

- What are the key metrics they need to improve? Ideally, this is answered in the outcomes

- Identify the type: Will they be mostly building, leading, or correcting?

- If a builder, look for someone with a bias for action, who understands the iterative process of the MVP approach

- If a leader, look for someone capable of galvanizing (for example, did the interviewees feel energized during their chat?)

- If a fixer, look for someone who is even-keeled, assertive, and determined.

- Clearly define the expected outcomes with 3 to 5 SMART goals. Decompose each goal into:

- Progression

- What is the evolution of this role? Will you ever need more of this role, could it spawn off different divisions, or the formation of a reporting team?

- What are the potential career advancements for someone in this role, both laterally and vertically, and within what timeframe?

Competencies Don’t build an actual person, as it can lead to biases during interviewing. Only Identify key traits and skills.

- Profile

- Title

- Salary

- Level

- Who they report to

- Who reports to them

- Key partners

- Location/Remote

- Alternatives What are the alternatives to hiring for this role? What happens if it takes too long?

External Job Description

Craft the external job description leveraging the Job Proposal document:

Must include the basics: Profile, mission, responsibilities, “needs to have” (no “nices to have”, either they are needed or not).

Include the interview process, what they can expect and how long it’ll roughly take

Questions for the potential candidate to ask themselves, accompanied with the answer that would indicate a good match. This is particularly useful to filter out if constructed properly. Consider the following toy example: The position might be for a chef, but if the restaurant is on a luxury yacht, then the question is not “Do you like creating new dishes?” but rather “Do you enjoy being out at sea for hours?”

Internal Scorecard

Create the rubrik that will be filled out by the interviewers as the candidate goes through the process.

- Goals and outcomes

- Company values

- Competencies

Here’s the process visualized:

Sourcing

Networking:

- This should be done by anyone in the company at any time, whether in person or LinkedIn.

The best position to be in is when you open a position and you already have several warm leads to reach to who have expressed interest in joining when a position that fits them opens up.

Interviewing

Tony Lucadello, was a professional baseball scout for the Cubs and Phillies during the 40s and 50s and is considered by some to be one of the greatest sports scouts ever. He had an approach that was different from the other scouts at the time, watching players from different angles around the field. According to him, there were 4 types of scouts:

- Poor: Wastes time looking for games rather than having a planned itinerary

- Picker: Emphasizes a player’s one weakness to the neglect of all strengths and ignores the potential within.

- Performance: Bases his evaluation on what a player does in his presence.

- Projector: Envisions what a player will be able to do in two or three years.

He believed that 5% of scouts were “poor”, “pickers”, and “projectors”, with the remaining 85% “performance” scouts. When crafting your interviewing team, consider them against these archetypes for the role that is being considered. Obviously the “poor” scout is useless, but depending on the expectations of the role, the “picker”, “performance”, and “projector” all have their pros and cons.

Best Practices

Interviewing is a skill that requires practice and also an affinity and aptitude. They can be draining and stressful, but don’t forget that the other person is considering a major life decision and likely interviewing for a while. Provide the experience you would like to receive when being interviewed.

“People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” - Maya Angelou

Before the interview

- Don’t read the notes of the previous interviewers as to not bias your own opinion.

- Use the restroom, drink water, bring the dog inside, mute Slack; prevent any possible interruption.

- Prepare your note taking document on your other monitor and write their name at the top

On the first 5 minutes of every interview

- Introduce yourself, who you are, what you do in the company

- Remind them of the length of the interview and what they can expect.

- Let them know that when they see you looking at another screen or typing, you are not answering Slack, but taking notes on your other monitor.

- Build some rapport and make the candidate feel comfortable.

Throughout the interview

- Take light notes, your focus should be on the candidate.

- Dig deeper with: “What”, “How”, and “Tell Me More”.

- Only interrupt if necessary to get the conversation back on track.

- Refrain from asking any illegal questions related to protected classes (age, race, gender, gender identity, religion, sexual orientation, marital or family status, pregnancy status, national origin, ancestry, physical or mental disabilities). Remember, they are interviewing you and your company as well.

At the last 15 minutes of the interview

- Remind them to ask questions and answer them.

- Thank them for their time.

Immediately after the interview

- Get some water, take a small break

- Finish writing down more detailed notes

- Based on your assessment and your assessment alone, write down one of the following “Strong Yes”, “Yes”, “No”, or “Strong No”. This will be used in the Debrief & Decision session.

Screening

Once someone applies, they promptly get scheduled for a call to get a quick alignment check on expectations, aspirations, and mutual fit.

Questions

- “What are you really good at professionally?”

- Check: Should match scorecard

- “What are you not good at or not interested in doing professionally?”

- Check: Should not match scorecard

- “What aspirations do you have for your next career move?”

- Check: Should be more about what they want to do, rather than what they want to receive

- “What makes a job engaging, fun, and motivating for you?”

- Check: Should match the environment of the role

- “What salary range do you expect from your next role?”

- Check: Should be within the budget

- “If hired, when is the earliest you could start?”

- Check: Should be within the required parameters

- “Let’s assume this goes well for the both of us and we do reference checks, how will your last couple bosses or colleagues rate your performance on a 1 to 10 scale when we talk to them?”

- Check: Reactions could quickly signal someone embellishing their resume

- “I would love to know about one thing you are passionate about/I would love to know about one of your most proud achievements, one that you can really brag about.”

- Check: The content is not necessarily that important, but how they convey the content. Extroverts and good storytellers could give a false positive and that is an acceptable risk. The objective is to unleash the candidate and have a conversation where you can get early signals for value fit.

Format

- One 30-minute phone call or Zoom/Google Meet session

- Conducted by either the hiring manager or someone from a Talent & Acquisition department (if there is one).

- Leave time at the end for questions from the candidate.

Topgrading / Behavioral

This interview should could follow the Topgrading methodology or the Behavioral-based technique.

If Topgrading

The interview asks the same questions (plus follow-up questions) throughout the last (or all) of the candidate’s career history. The main questions ask candidates about successes, mistakes, key decisions, key relationship, their manager’s strengths and weaker points, how their manager would rate them, and why they left the job. The theory behind this interview method is that the Threat of Reference Check (TORC) will cause many low-performers with exaggerated resumes to drop out, leaving a pool of theoretically honest and successful candidates. Candidates who are more willing to discuss the entirety of their career provide broader insights to interviewers.

Questions

- “What were you hired to do?”

- Check: If they can answer this

- “How did you define your priorities?”

- “What key metrics did you focus on?”

- “What were low points/What was your biggest mistake/Biggest lesson learned?”

- Check: Dig for growth and self reflection, no ego, no blame, growth and vulnerability

- “How were your team relationships?”

- Check: Lone wolf, team player, blame, collaborator

- “What accomplishments are you most proud of and how did you accomplish them?”

- Check: Are they outcomes or events/activities (fluff)

- “Why did you leave your job?”

If Behavioral

The interview focuses on a candidate’s past experiences, behaviors, knowledge, skills and abilities by asking the candidate to provide specific examples of when they have demonstrated certain behaviors or skills in the past as a means of predicting future behavior and performance.

Questions

- “How do you like to interact and communicate with your team?”

- Check: Do they mention daily standups, preference for collaborating, pair programming, pair up for ideation, triaging, etc

- “Tell me about a time you were most satisfied with your work?”

- “Tell me about a time you were most dissatisfied with your work?”

- “How do you manage burn out?”

- “What are key actions and steps you take to ensure quality?”

- “Have you ever proposed a new process/technology?”

- “How did you evangilize it?”

- “How did you get people to try it?”

Format

- One 60-minute Zoom/Google Meet session

- Conducted by hiring manager.

- Leave time at the end for questions from the candidate.

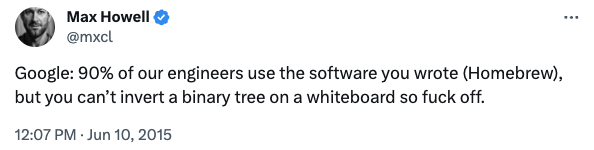

Focused / Technical

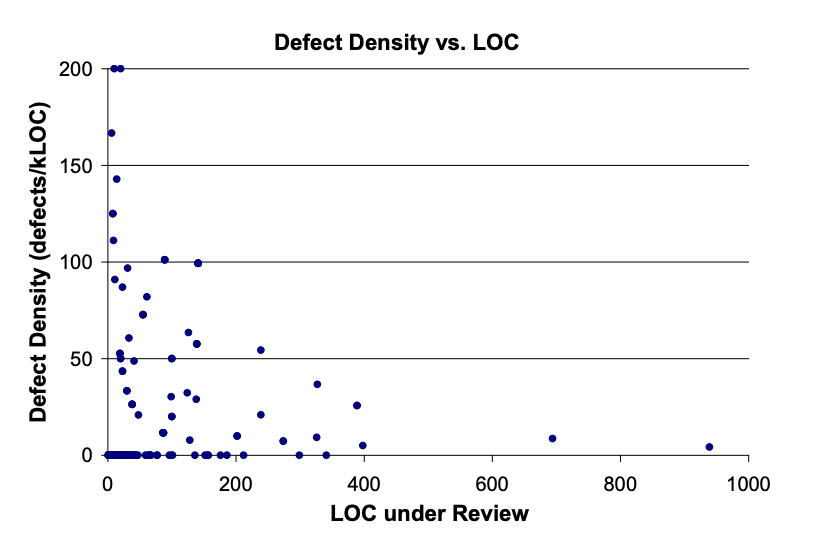

This is where you dig into the meat of their role. This interview will be very different depending on the role, department, seniority. However, the important consideration here is that it should resemble the actual work as much as possible, and not a Leetcode or HackerRank problem. If not, it can be very easy to pass on great talent:

https://twitter.com/mxcl/status/608682016205344768

https://twitter.com/mxcl/status/608682016205344768

Interviewing.io publishes great insights about technical interviewing that are worth repeating:

Regarding interviews

- Interview should feel collaborative and not adversarial.

- The purpose of every interview is to “see if we can be smart together”.

Regarding a good technical interview question

- Layered Complexity: Where the initial question starts off simply and it builds from there. This also allows for quick benchmarking, as the lastly reached layer number is quick signals into the candidate’s technical ability.

- Real-world Relevance: Crafting the question or exercise in a way that retains the essence of the company work

- Algorithmic Leetcode or HackerRank questions are not preferred, but if still chosen, there should be some nuance and depth to make them fresh and interesting.

- Question quality (as assessed by interviewees) was found to be an extremely significant indicator for if a candidate wanted to move forward (whether the candidates did well or poorly).

Regarding general insights

- Interviewer being good at providing great hints (well-timed, didn’t give too much away) was found to be another extremely significant indicator for if a candidate wanted to move forward (also adjusted for candidate performance).

- Self perceived notion of good performance was very statistically significant as well for wanting to accept an offer as well as wanting to work with the interviewer.

- Resumes are a low-signal document.

- Technical interviews are a high-noise activity.

Other alternatives to coding exercises

- Pair programming sessions for a redacted feature or bug that is a stripped down version of something they would deal if hired.

- Live coding a reduced project that once again, is a toy version that maintains the essence of the real work.

- Portfolio discussion of a project that the candidate can speak to. This one does require a skilled interviewer to know which questions to ask to gain valuable insights.

- Take home projects can solve the uncomfortableness of coding while someone is looking over your shoulder. However, depending on the scope, they are often perceived as free labor or too much of a time commitment.

Potential Format:

- One 60-minute programming session

- One 30 to 60-minute system design session

- One 30-minute code review session

- Conducted by experienced engineers

One of the most debated topics for across engineering organizations is whether managers/leaders should maintain technical activities. Regardless of the expectation of coding, code reviewing, and architecting features and infrastructure, it is generally agreed that they should come from technical backgrounds and still retain that knowledge. Appendix A is a list of question to assess this ability.

Values

This is the last interview and it might seem like calling it an “interview” is a stretch. This is when the candidate has a chat with the CEO or top leader in their department to truly identify if the is a strong mutual value fit. The questions might change based on the values of the organization, but a list of common and important values alongside a couple of questions to get a signal on them from the candidate can be found in Appendix B.

Format

- One 30-minute phone call or Zoom/Google Meet session

- Conducted by executive or high-level leader in the organization

- Tell the candidate to ask questions as they chat, no need to wait until the end.

Closing

While everyone involved in the process should have been selling the company, the role, and the opportunity, the explicit action of closing becomes imperative the moment that it is decided you want to hire this person.

Losing out on a great candidate after going through the entire hiring process can be crushing. Once you get a sense that this person will likely reach the offer stage, you need to ramp up selling the opportunity to facilitate the moment of closing.

The urgency is imperative, as likely, you have the second-best candidate waiting without an offer while your first-choice is making their decision. Ending up losing both is devastating.

These are the key factors most people care about when making a decision. Throughout the conversations, identify which ones are the top priority for the candidate and make sure to sell them on those as they move through the stages:

- Company trajectory

- How much this role will add to their professional growth

- Culture and value fit

- Work/life balance

- Match with their team

- Location or remoteness

Reference Check

It is useful to consider the reference check as part of closing. Ideally, this step does not yield surprises but rather provides an opportunity to chat with individuals who can give you actionable information to not only set up the future new employee for success but also, to close them.

You should only contact “direct references”, and do not pursue “indirect references”. Understandably, the references provided by the candidate are most likely only going to speak highly of the person, but again, the objective of these calls shouldn’t be to disqualify the applicant. If that is the case, there is a major flaw in the interview process that needs to be corrected. What you want is to get third-party perspectives on what motivates this person, what makes this person shine, and what they struggle with, so you can develop a plan of action to make them grow and succeed in your company.

You should get 3 to 5 references, at least one of each for the following:

- Someone they reported to

- Someone they worked with

- Someone that reported to them (for managing roles)

Questions for someone they reported to

- “What were their most important achievements?”

- “What were their biggest learning moments?”

- “What was the most effective way to provide them feedback?”

- “Did you ever disagree? How did they handle it?”

Questions for someone they worked with

- “From your experience, what was this person really good at?”

- “Back when you worked together, what were their areas of improvement?”

- “Did you ever disagree? How did they handle it?”

Questions for someone that reported to them

- “Is there any professional growth that you can attribute to this person?”

- “What was their way of giving you feedback?”

- “Is there one main thing you learned from this person?”

- “Did you ever disagree? How did they handle it?”

Pre-Offer

It can be very useful to get a signal on the level of interest by the applicant before making a decision to make a decision on whether to extend an offer and the final details of said offer. One of the most effective methods is for the executive or leader performing the Values Interview to be ready to ask the following question in case they feel they would be a “Yes” at the Debrief & Decision session.

“In the case that we tendered an offer that made sense for you financially, do you see yourself joining our company?”

- If a “yes” with no hesitation:

- You are likely their first choice.

- If unsure:

- Ask what questions could you answer that could help clarify their decision-making process.

- Consider asking if they currently have any offers on the table that they are considering.

- If the candidate says they need an offer first:

- Reinforce the aspect of the question of “let’s consider that the offer made financial sense for you”. If still no concrete answer, ask if they have a timeline for when they are expecting to have a decision made.

Debrief & Decision

Ideally scheduled the earliest possible after completing the Reference Checks, as human recall is notoriously susceptible to distortion over time.

Procedure

- Everyone who participated in the interviews for that candidate must attend.

- Everyone must initially reveal their “Strong Yes”, “Yes”, “No”, “Strong No”. If there is one “Strong No”, the meeting can be shortened and most participants free to leave.

- Everyone gets around 2 to 5 minutes to present their assessment of the candidate.

- The hiring manager makes a decision.

Offer

You want to minimize or eliminate the possibility of negotiating. The unfortunate reality of this step is that at the beginning of this relationship, both parties have conflicting maxims of utility: The candidate wants to get the highest compensation possible, and the organization wants to spend the least possible. Moreover, the moment an offer is extended, your next-best candidate is in limbo. You should never extend more than one offer at a time, as rescinding it later will reflect incredibly poorly on the company and will likely result in a less-than-stellar reputation pretty quickly.

Procedure

- Prepare the offer details and schedule a call with the candidate.

- Be enthusiastic, tell them that the team is excited about the possibility of working with them.

- Proceed to say: “After concluding an analysis of market compensation for where you fit within your role, if we were to make the following offer <Explain the compensation details, cash, equity, benefits>, would you accept it?”

- If the answer is yes, then email them the offer right away.

- If the answer is “I need the offer in writing”, they likely want to negotiate or shop around with your offer.

- Explain the truth, how the organization considers the people they hire to be their biggest asset, and therefore the company makes sure to offer the best package possible. Not doing so means that negotiating is an option, which is another way of saying “We believe you are worth X, but we want to try to get you for X - Y”.

- You can also explain how the moment you extend an offer, no other offers are going out the door, which opens up the possibility of losing the next-best candidate.

- If the answer is “no” to either scenario or repeated attempts to negotiate, thank the candidate and tell them that you understand if they consider the offer to not match the value they could provide and that you wish them the best in their search.

Onboarding

The moment the candidate accepts their offer is when onboarding begins. This person just made a big life decision and first impressions are lasting. Make sure they don’t feel forgotten or confused about next steps.

Keep the excitement going

- Have a prepared email with details on next steps.

- Have them chat with people in their team.

- Have a swag package ready to be delivered overnight.

- Send them a video recording of all the excited reactions during the last meeting when the hiring manager told the team that the candidate accepted.

Onboarding is critical. If not done right, there are 3 likely outcomes

- The person will quit.

- The person will be ineffective.

- The person will be resentful.

Be prepared with a template for a 30/60/90 day plan:

- With specific, measurable goals.

- Relevant to the role.

- Should be collaborative, with review and buy-in from new hire.

- Achievable, with early wins to build confidence.

- A good rule of thumb is for the first week to revolve around gathering context, get set up, start relationships, and ask questions; and for the second week to get a tangible, concrete (albeit small) win.

Review 30-60-90 Day Plan.docx for an example template.

Measuring

Unfortunately, while hiring is one of the (if not the) most influential and critical action for your organization, little is done to measure, learn, and improve it. Understandably, the way you refine or improve any process, is by measuring successes and failures. In this case, we have an asymmetrical access to the data, we know the performance of the people hired but we don’t know the performance of the people passed on.

What can be improved or what does it mean to improve hiring? It means to improve the hiring process such that it:

- Doesn’t pass on strong candidates, only on poor candidates.

- Hardest one to measure as it requires checking where the candidate ended up after about a year from their application.

- Takes the least amount of time and resources as possible to yield the results.

- Expensive to measure as it requires experimenting with the process.

- An alternative is to review the scorecards for each hire at their one year performance review. Look for any statistically significant interviews or interviewers that most consistently match the performance review.

- Yields more people being incredibly successful than unsuccessful.

- Same as the previous one.

- Results in high candidate satisfaction, regardless of outcome

- Send them an anonymous survey with a $20 gift card upon completion that doesn’t share the results until at least 10 candidates have responded with the following questions:

- How good were the questions? (1 to 5)

- How helpful was your interviewer in guiding you to solutions? (1 to 5)

- How excited were you to work with the company? (1 to 5)

- How was the length of the process (too short, about right, too lengthy)

- Free form comments

- Send them an anonymous survey with a $20 gift card upon completion that doesn’t share the results until at least 10 candidates have responded with the following questions:

Effective People Leadership

This will be tackled in three ways:

- Leading engineers

- Leading leaders

Leaders must deliver business goals through the leverage of :

- Performance

- Producitivity

- Happiness

However, this is only half of the equation. For these people to function and deliver, they need to work as a team. And if you want them to be a high-performance team, there are several components that must be handled:

- Identity Definition

- Goal Setting

- Collaboration & Dynamics

- Conflict Management

- Decision Making

Lastly, there are unique and new challenges in leading and team building in a remote world. The last section summarizes several tips.

Leadership Principles

Depending on the scope of leadership (e.g.: of a team, of a department, of an entire organization), the implimentation of these principles shifts with the focus. According to Ford, there are three effective leadership focuses:

- Tactical leaders focus on solving straightforward problems with operations-oriented expertise.

- Strategic leaders focus on the future, with an ability to maintain a specific vision while forecasting industry and market trends.

- Transformational leaders focus less on making decisions or establishing strategic plans, and more on facilitating organizational collaboration that can help drive a vision forward.

When leading at scale, your output transitions from tactical and specific, to strategic and holistic. Broad over deep, abstract over details. As you traverse down this list your technical expertise is less relevant than your ability to influence motivate, detect patterns, competently assess trade-offs, align interests and goals, organize people, build effective processes, policies, and structures.

This is by no means an all-encompassing list of all activities and behaviors of a great engineering leader, but they have worked for me:

Act on High Leverage: Prioritize activities that only you can perform and that have the most significant impact, rather than merely focusing on what you’re good at.

Align: Ensure that the goals of every team align with each other. Even if each team individually meets its goals, misalignment can lead to inefficiency or decline.

Be Vulnerable: Embrace mistakes as part of the growth journey and don’t fear them. Worry more about failing your team and customers than making mistakes.

Coach and Mentor: Provide guidance and mentorship to nurture your team’s growth and development.

De-risk Everything: Your teams work to find the best solutions, and your role is to identify the balance between achieving the best outcome and managing risks effectively.

Delegate: Divide complex tasks and delegate responsibilities effectively. Only engage in tasks that require your unique expertise.

Detect: While your teams focus on specific issues, it’s your responsibility to see the bigger picture and identify any blind spots or processes that are stuck in the status quo.

Develop Contextual Intelligence: Develop an understanding of different cultures to work effectively in diverse environments.

Diversity of Thought: Create an inclusive environment that values diversity and different perspectives.

Empower: Focus on scaling your efforts to empower and unleash the potential of others.

High-Standards Culture: Lead by example and foster an environment of excellence and compassion. Ambitious goals require astounding support.

Knowledge not Hierarchy: Priority and importance is not based on seniority or title. Allow those with valuable knowledge and experience to have a prominent voice.

Make Yourself Obsolete: Your aim is not to render yourself unnecessary due to incompetence but to build self-reliant teams.

Manage Conflict: Understand human behavior to navigate constructive disagreements effectively.

Negotiate: Master the art reaching mutually beneficial outcomes. No “zero-sum” games.

Never the Expert: Foster a mindset that views challenges as opportunities for growth.

The Right Focus: Build your team’s identity around solving problems, not just delivering solutions.

Prioritize: Distinguish between urgent but unimportant and important but not urgent tasks.

Satisfice Decisions: Focus on choosing the most practical solution, rather than aiming for the ideal one. Make high-level strategic decisions and empower your teams to decide on the detailed implementation.

Leading Engineers

There is a vast body of research, literature, and teachings on the subject of leadership. Particularly, of individuals with specialized skills and knowledge that, ideally, exceeds yours. Combined with the never-ending need to coalesce multiple groups of talents to pursue a common goal, it can become an exercise in futility to only lead what you are an expert on.

Leading is not:

- A reward for knowing how to do something better than others

- Telling someone what to do

- Micromanaging their every move

- Abandoning individuals when they encounter challenges and favoring only top performers.

Leading is:

- Understanding who a person is

- Grasping what motivates them

- Nurturing their personal and professional growth

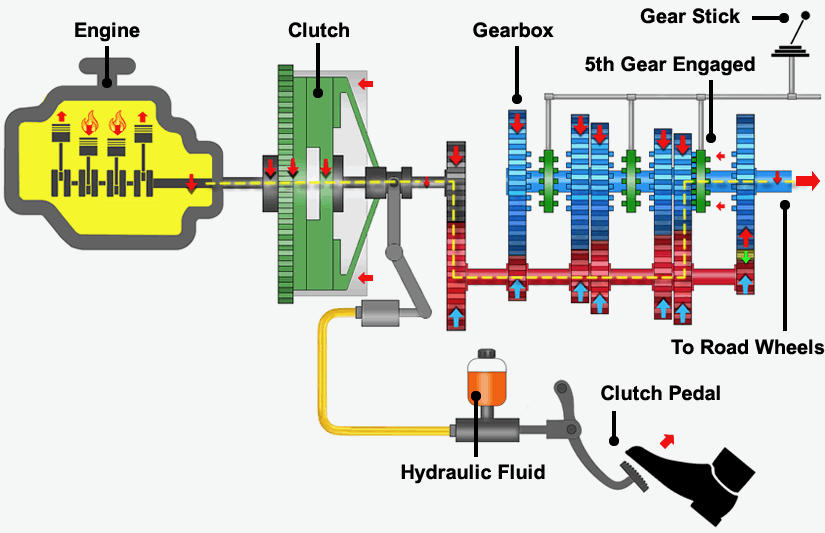

More importantly, why is it needed at all? Engineers are clearly smart, can’t they lead themselves? I find a useful analogy in a vehicle’s manual gearbox.

https://learndriving.tips/learning-to-drive/how-to-change-gear-in-manual-car/how-manual-car-gears-work/

https://learndriving.tips/learning-to-drive/how-to-change-gear-in-manual-car/how-manual-car-gears-work/

A transmission has multiple gears, each facilitating the optimal distribution of power to the wheels through a clever combination of gear ratios. The presence of a clutch allows for the imperfect action of shifting gears while the engine spins at thousands of revolutions per minute. However, for each gear at rotating at a specific wheel speed, there’s a corresponding engine velocity (RPM) at which you can shift without a clutch. This is very challenging and risky, and a slight misstep can result in gear grinding and damage to the transmission. The clutch bridges the gap, allowing the engine and transmission to operate independently, yet harmoniously. A (good) leader performs the same function. They do not meddle with the engine or the transmission; instead, they enable each component to perform at its best.

I try to avoid the word “manager”. It is a remnant from the industrial revolution where work was mechanical but done by humans. Factories filled with replaceable low-skilled or unskilled laborers who just needed to keep the floor operating. You manage the unexpected, you manage scenarios and circumstances, you manage projects, and you lead people, you lead towards goals and ideal outcomes.

Motivation

This section is informed by Dan Pink’s book “Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us”. It’s essential to understand the two primary sources of motivation:

Intrinsic (from within)

- Autonomy

- Mastery

- Purpose

Extrinsic (from outside)

- Money

- Praise

- Accolates

Historically, contingent motivators were highly effective when work primarily involved simple, mechanical tasks that demanded more focus than creativity. These contingent motivators rewarded task completion and its speed. For example, “Build 10 chairs in a day and earn \$100, build 20 chairs in a day, earn \$250.” Entire management processes and policies built around these incentive structures were prevalent during the industrial revolution when work mostly required staying focused, adhering to straightforward rules, and pursuing known solutions.

However, when tasks involve cognitive functions beyond the rudimentary, motivation through extrinsic rewards ends up being counterproductive. Work that necessitates creativity, problem-solving, and inventiveness responds more favorably to intrinsic motivators.

- Autonomy is the desire for independence and the ability to have control of our lives.

- Mastery is the desire to become proficient and excel at something that matters to us.

- Purpose is the desire to connect our talents and contributions to a greater cause.

In practice, you should consider the nature of the motivation you seek to instill:

- If you require compliance, managing and deploying extrinsic motivators might be appropriate.

- If you aim for genuine engagement and a high level of commitment, the path to success involves leading and creating an environment that fosters intrinsic motivators.

Performance

One of the most critical activities as a leader of a team, is to address early signs of low performance.

If someone is failing at something they were good at, there is a human issue that needs to be addressed.

If someone is failing at something they’ve never done before, there was a leadership failure for putting the person there before they had the tools, knowledge, and skills.

There are many causes for low performance, but the most effective tactic to correct it is to treat it like physical therapy:

- Build up confidence with small feedback loops of wins

- Build a plan together with specific time frames, goals, and agreements

Feedback

One of the most pivotal skills for any leader is the art of providing feedback. Effective feedback requires a delicate balance of several key elements:

High degree of empathy: Understand the emotions and perspectives of the person receiving feedback. Empathy is the bridge to fostering a supportive feedback environment.

Candor and respect: Candid feedback is crucial, but it must be delivered respectfully. Be honest without being harsh or judgmental.

Genuine care in the growth of the person: Convey a sincere commitment to the individual’s growth and development. Your feedback is not about pointing out flaws but helping them improve.

Feedback should meet specific criteria:

Be Specific: Address particular behaviors or actions rather than making general or vague statements.

Delivered Timely: Give feedback as close to the observed behavior as possible. This ensures that the context is fresh and vivid.

Focused on Actions, Not Assumptions: Base your feedback on observable actions, avoiding assumptions or inferences.

Open to Correction: Be humble and willing to be corrected if new information comes to light when you provide feedback.

To structure your feedback most effectively, consider this expansion from the SBI model (Situation, Behavior, Impact, Correction, Support, Commitment):

“In our last team meeting (Situation), when discussing the project timeline, you interrupted multiple team members and spoke over them (Behavior). This prevented us from effectively sharing our ideas and caused frustration among the team (Impact). I need you to improve your communication and collaboration skills (Correction), which I know you can do (Support), and I am committed in helping you do that (Commitment).”

It’s vital to acknowledge that receiving feedback can trigger an amygdala response, a sensation of “fight or flight” with fear or anger. When this happens, higher cognitive functions are reduced causing the person to not be open to constructive comments. Seek buy-in before engaging: “Is now a good time for us to talk for a few minutes? I’d like to share some feedback.” If properly hiring for value fit, people with growing mindset and humility will receive this positively.

Remember that effective feedback should be a regular and private practice. Public positive feedback can be a powerful motivator, but be mindful of individual preferences as some team members might prefer a more private acknowledgment.

Plenty has been studied and published on the subject of feedback. The following are some useful summaries:

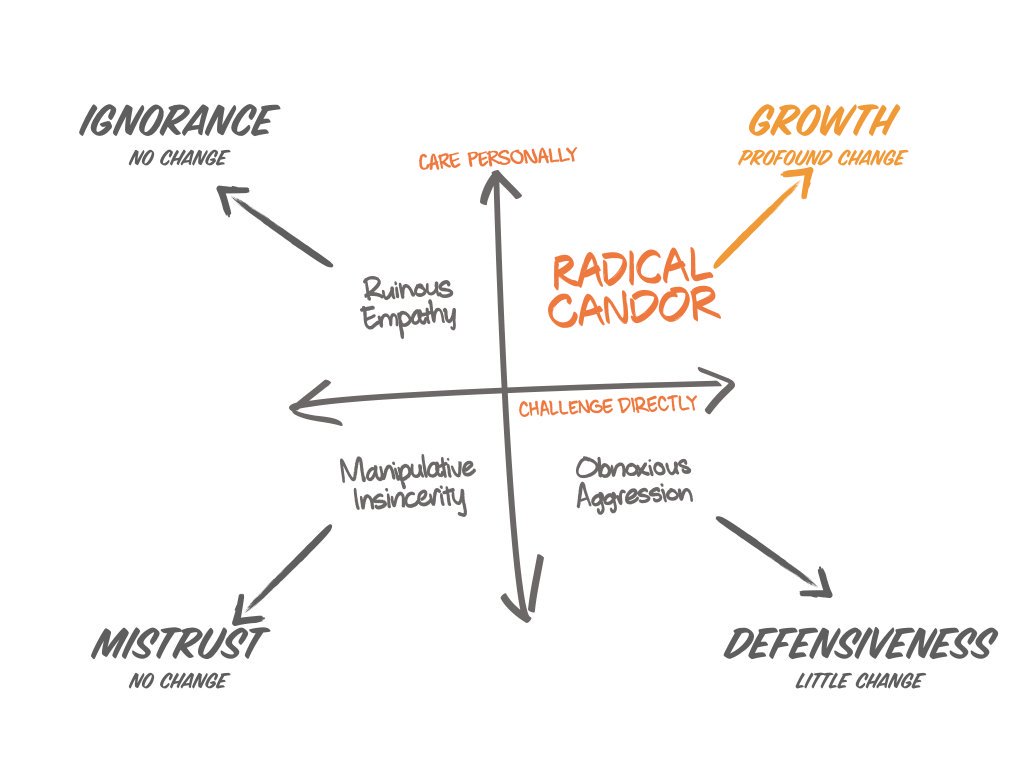

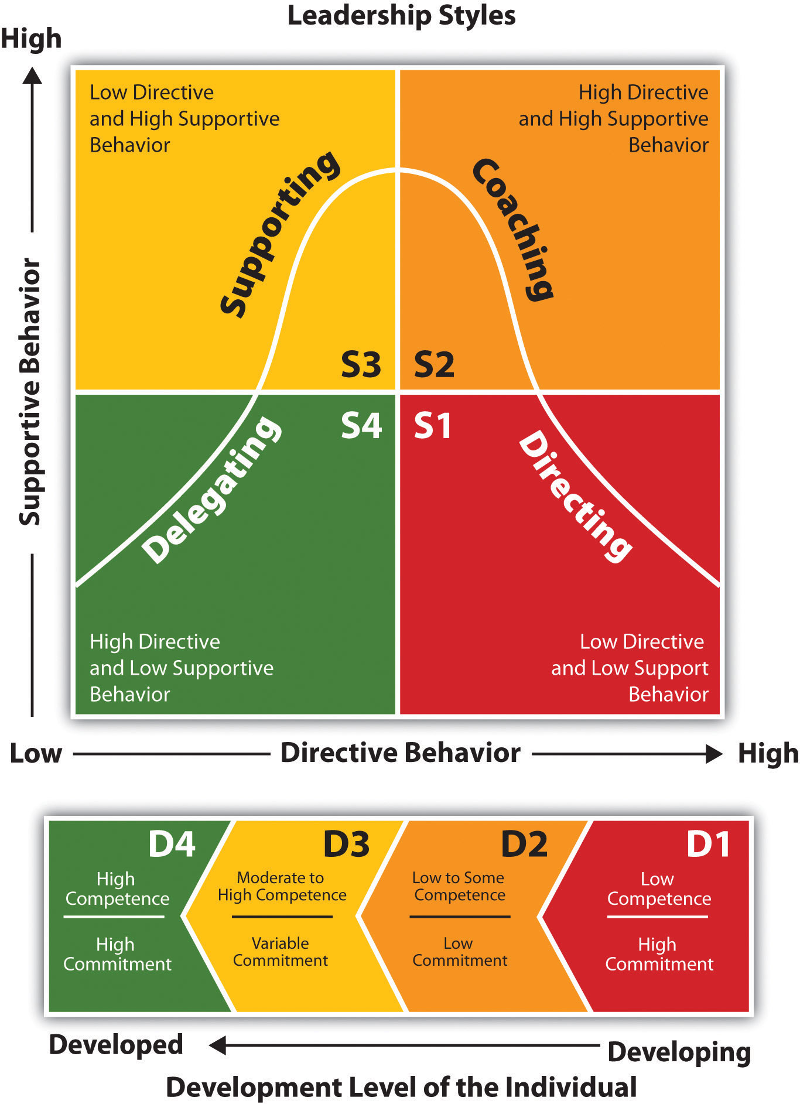

A well known “Critical Positivity Ratio” (also known as the Losada Ratio), which stated that there was a 5.8 to 1 positive-to-criticism ratio for high performing teams and 3 to 1 for professional athletes, has been retracted and its claims deemed unfounded.